Excerpt from Ross W. Jamieson's The Essence of Commodification: Caffeine dependencies in the early modern world. Journal of Social History, Winter 2001

Yerba mate and the Jesuits

Yerba mate and the Jesuits

Not all the caffeine drinks encountered in the course of European colonial expansion came to be accepted for consumption in Europe. In the Americas there were several plants besides cacao that contained caffeine and were known to the indigenous inhabitants, none of which ever reached commercial distribution in Europe. The most economically important of these exclusively New World caffeine drinks was yerba mate. This is a tea made from the leaves of a holly (Ilex paraguariensis) harvested in prehispanic times along the Parana-Paraguay river system.

Early Spanish settlers along this river system had taken up the pre-Columbian practice of drinking wild yerba mate as a tea. As with cacao, they acquired the habit from the people they had conquered. Unlike cacao and coffee, yerba mate was not a domestic plant when first encountered by Europeans. Instead it was harvested from wild stands. Initial Spanish colonization of the Parana-Paraguay system was tied closely to Jesuit missionization efforts. Jesuit policy encouraged large-scale plantation agriculture on the seventeenth century South American missions, as a method of using indigenous labor to produce marketable commodities, and make the missions both self-sufficient and profitable. The Jesuits realized the great economic potential of yerba mate, and from the 1650s to 1670s successfully founded yerba mate plantations at their missions.

When Europeans arrived in the Parana-Paraguay there was no existing market for yerba mate beyond the local region. With the domestication of the plant as a plantation crop the Jesuits also contributed to the creation of a commercial market for it. By 1700 the drink was popular throughout the Andes and the Rio de la Plata. As with cacao, yerba mate was developed as a plantation crop to serve a consumer market within the colonies, rather than for shipment to Europe. The product was shipped down the Parana-Paraguay system, then either to Santa Fe, where it was hauled overland to Chile, Upper Peru, and Lima or continued by river to markets in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

Yerba mate was never introduced to the European market--perhaps because it only gained commercial prominence in Spanish America after 1700, long after tea, coffee and cacao had become available in Europe. The expulsion of the Jesuits from the Spanish colonies in 1767 ended the cultivation of yerba mate on the mission plantations. The European Enlightenment criticism of the Jesuits that led to their expulsion was in itself partly based on their successful plantation economies worldwide. When they were expelled from all Spanish dominions their missions on the Parana-Paraguay were abandoned. This caused huge changes in yerba mate production, as the missions were transferred into royal and private hands. Massive exploitation and near-slavery of the local Guarani population led to their abandonment of the missions, and the temporary end of yerba mate as a plantation crop.

It was fairly simple for commercial growers to transplant cacao and coffee to new plantations, but yerba mate proved to be a finicky crop. Spaniards apart from the Jesuits had little success in growing it, so production after the Jesuit expulsion came largely from the harvest of wild stands in Paraguay. The town of Concepcion, founded in 1773, became the northern mate port, with land access to the stands of wild plants in the hinterland. Yerba mate was the only caffeine crop ever harvested commercially from wild stands in large quantities. Harvesting of the plant was a speculative enterprise, with Indian debt peons spending months in the forest harvesting, drying and bailing the crop. Many members of these work parties died.

The crop was sold regionally in South America, never gaining European markets. The Bourbon reforms massively increased the volume of the yerba mate trade in South America, as it did with the cacao trade from the Guayas region. The creation of the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata in 1776 meant that the merchants of Buenos Aires took control of both the yerba mate production zones in Paraguay, and one of the major consumer markets, in Alto Peru. Free trade and tax reforms in 1778 and 1780 made exports far more profitable.

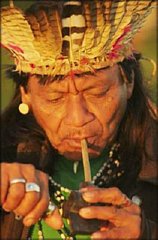

By the 1770s yerba mate was a popular social drink throughout the Andes, served at all hours of the day. The tea (or yerba) was traditionally drunk from a gourd (or mate), sipped through a straw known as a bombilla. By the 1770s this market had penetrated as far north as Cuenca, where the traditional gourd with silver straw began to appear on elite tables in this tertiary northern Andean city. Several examples of mate gourds mounted in silver with a silver straw have been encountered in late eighteenth century inventories from Cuenca. There was a female association with this form of Andean consumption, a contemporary observer stating that "... there is no house, rich or poor, where there is nor always mate on the table, and it is nothing short of amazing to see the luxury spent by women on mate utensils." The gendered nature of the consumption of caffeine drinks in the early modern world has not been extensively studied outside Europe, but in the case of yerba mate in the Andes the association is with female, and domestic, consumption.

Yerba mate thus provides us with an example of a caffeine beverage crop with a unique historical trajectory. Developed as a plantation crop by the Jesuits to supply a South American market, it reverted to a system of commercial harvesting of wild plants after the Jesuit expulsion. The difficult transplantation of the wild plants meant that domestic plantations were not easily founded, and the wild plant harvest remained important for much of the commercial history of yerba mate. This situation continued until the 1890s, when large yerba mate plantations were successfully developed in the southern Mato Grosso to serve the modern regional market.